CHAPTER ROOM SERMON FOR CORPUS CHRISTI

23rd June 2019

Rather than trying to find thoughts and words to match the wonder of the Lord’s bounty in leaving us the immense gift of his very Body and Blood as our food and drink, it seemed preferable to take a more humble approach and share the story of how the Feast of Corpus Christi came about. All the more so in that we Cistercians have a vested interest in the matter, and more particularly we in Mount St Joseph.

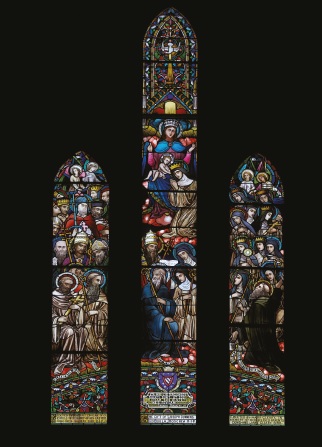

When you look way up at the three-light window over the main door of the Church, and concentrate on the right hand light funded by Mary Cleary of Birr, with St Benedict at the bottom and a plethora of Cistercian women saints above him, you see about two-thirds of way up, on the left of this light a crowned nun with above all things a Monstrance in her hands, with a gleaming white Host at its centre. That nun is Saint Juliana of Mount Cornillon, and that window is in place since 1892. Weren’t our early monks of Mount St Joseph way ahead of their time in so depicting Juliana? And why did they do so? It is because it was through her extraordinary devotion to the Lord in the Eucharist that the Feast of Corpus Christi was introduced. Indeed you may remember when the Eucharistic Congress was held in Dublin in 2012 we Roscrea monks produced a little book-mark with our image of Juliana, a book-mark on which Fr Dermod McCarthy, past student of our College, commented during his television presentation of the Papal Delegates Mass in Croke Park.

Not everyone agrees that Saint Juliana was a Cistercian. In fact the 1999 edition of ‘Butler’s Lives of the Saints’ reduces her to ‘Blessed’ and tells us that the monastery of Mount Cornillon in which she was a nun and later prioress, was Augustinian, though a footnote describes the source of its information as “fairly reliable”. Seeing that for many in our day Google has the final say, and what do you think it offers but ‘The Life of St Juliana of Cornillon’ by George Ambrose Bradbury, monk of Mount St Bernard Abbey, published in 1873. Google does not content itself with a reference to this volume, but gives us all 200 pages of its text! We have this book in our library. Fr George had no doubt whatever that the Mount Cornillon Juliana entered and where she was prioress, was Cistercian, though he goes to such rounds to emphasise this that one tends to wonder with Shakespeare: “methinks the (good man) doth protest too much”! However we have another book in the library which agrees with Fr George. It is a great 1,200 page Latin history of our Order, “Cisterciaum Bis Tertium” composed for the six hundredth anniversary of the Order, printed in Prague in 1700. The five pages devoted to our Saint says: “Divae Juliana quinquenni ad Cistercium convalanti … ” (the blessed five year old Juliana who came hastily to Citeaux …) Interestingly this volume also tells us that she was an assiduous reader of St Augustine and St Bernard. Perhaps in these more ‘ecumenical’ times we should all be encouraged by Juliana herself to love and read both Augustine and Bernard, and that Augustinians and Cistercians should all be happy to share ownership of Juliana of Cornillon, and something of her wondrous love of the Blessed Sacrament.

Juliana was born in 1193 near Liège in present-day Belgium, close to the German and Dutch borders – a true European. Both her parents died when she was a five year old, leaving her and her six year old sister, Agnes orphans. Their guardians placed both of them in the Convent of Cornillon. She was an exceptionaloly pious young girl, in the best sense of the word. Besides her extraordinary devotion to the Blessed Eucharist, she endeavoured to have a great personal love for Our Lady. Nevertheless she had her feet on the earth. At her own request she worked in the monastery cow-house, caring for the stock and cleaning the byre.

As a 14 year old, like St Thésèse, of the Child Jesus centuries later, she begged to be admitted into the Community as a nun. She was accepted. She studied Latin in order to be able to read the Scriptures and works of the Fathers of the Church, and to do her lectio. Over the years she was drawn more and more into the contemplative direction, finding an altogether special attraction to the mystery of the Body and Blood of Jesus. She was gifted by the Lord with many mystical experiences, and gifted too in her dealings with people who came for her advice or her prayers, which often brought healing to bodies and souls.

Not surprisingly, besides the wondrous gifts and graces the Lord bestowed on her, there were sufferings in proportion – bodily pains, weakness and languor, but the keenest pain Juliana experienced, we are told, were the offences that are daily committed against the Divine Majesty, even to taking in her wondrous humility, the guilt of these on herself, so seeing herself as the greatest of sinners.

In 1222 Juliana, as a 29 year old was unanimously elected Prioress or Superior of Cornillon, a responsibility which she took on with total commitment. While most of the nuns found her governing lead them to a new depth of spirituality, there were however a few who did all in their power to undermine her. But in time her prayer, her meakness and her patience won them over.

Having been commissioned by the Lord in a vision to work towards establishing a special Feast to celebrate the Blessed Sacrament, her devotion to the Blessed Sacrament was so great that nothing could give her greater pleasure, but for the life of her, she could not see how she a poor obscure nun, could accomplish such a task. She implored the Lord to commit the task to a worthy and competent person. Twenty years had passed since she had first had this vision, when she doubled her prayer and fasting to have the task removed from her, the answer came from the Lord that she was the one to act.

At long last she laid her soul bare to a learned Canon, John of Lausanne, who accepted her mission to have the Feast of Corpus Christi introduced. He referred the matter to a group of experts including the Provincial of the Dominicans, the Bishop of Cambrai and the Chancellor of the University of Paris, who unanimously agreed that the Feast should be introduced, to excite the faithful and reanimate the devotion of all Christians to the Holy Sacrament of the Altar.

Juliana accordingly considering it was now time to compose an Office for the new Feast, charged John, a young member of the men’s monastery of Cornillon, as it was in fact a double monastery. John declared his incapacity and ignorance of the Fathers, but Juliana offered continual and most fervent prayer and in a short time John composed a beautiful Office, convinced that all its beauty and devotion came not from him, but from the Lord.

However when the whole affair became public news, opposition to the idea of this new Feast built up in Liège, stirred up by Roger a new malevolent prior of the mens’ Monastery of Cornillon. It reached such a pitch that Juliana, accompanied by a few companions had to leave her beloved monastery and go into exile to St Martins. It is recorded that through all this turmoil Juliana retained a “heroic patience and meakness, perfect obedience, and sincere and profound humility”, and yet her zeal for the institution of the Feast of Corpus Christi never relaxed.

While very sympathetic to the cause, Robert the Bishop of Liège, was very slow to act, but eventually he instituted the Feast for his diocese and ordered 20 copies of the Office composed by John, who by now was Prior of Cornillon, to be distributed through the diocese. The Bishop had fixed the first celebration to be on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday. There was still a general lack of enthusiasm. However on that day in 1247, the Canons of St Martin first celebrated the Feast of Corpus Christi with all possible splendour, magnificence and devotion. One can imagine the depth of joy that filled the heart and soul of Juliana. But her troubles were not over.

The deposed Prior, Roger was back making trouble once again, so that Juliana had in 1248 to leave her beloved Cornillon, this time for good, and without a word against her persecutors, because as she said “I desire their salvation as much as my own”. Her first place of refuge was the Monastery of Robertmat where she was warmly welcomed by the Abbess – but it was too near Cornillon and trouble followed, then to Abbey of Val Notre Dame – but still too near. Then to Namur and to the Cistercian Abbess Himana of Salsines welcomed her and her companions, and to whom after a few years Juliana promised obedience.

Seeing that at Cornillon the elected superiors of both womens’ and mens’ communities were referred to as Prioress and Prior, while at the Cisterican monasteries the superiors were Abbesses, one is lead to believe that the Cornillon monasteries were in fact Augustinian and that it was in her years of exile that our right to refer to Juliana as de Ordine nostro, (of our Cistercian Order), especially when she made obedience to Abbess Himana. And mighty proud we are of that, and thankful to God for having among us a beautiful person who had such an abiding love for Christ in the Blessed Sacrament, and who was the prime mover in having the Feast of Corpus Christi introduced. A fresh consideration of the appropriateness of this devotion is presented to us Cistercians today, more especially as it is a devotion which is spreading widely through Irish parishes in recent years.

Before leaving our Juliana, she had still more to suffer during her Cistercian years: all four of her Cornillon companions died at Salsines, next because of further troubles that Community itself had to disperse – Juliana and Himana went to Fosses where she died 5th April 1258. She was buried, at her own request, at our Cistercian Monastery of Villers. It was six years later, 1264 when Pope Urban IV, a one time Archdeacon at Liège, having asked Thomas Aquinas to compose his new office, most of which we still use, instituted the Feast of Corpus Christi for the whole Church.

Laurence Walsh ocso